Buccah Jankes, left and Ray Wilkes were the key personalities behind the nursery schools. They are here with United Sisterhood leader Joy Raphaelly

The politics of teaching toddlers

The United Sisterhood’s biggest project was to run five nursery schools. This proved more complex than anyone expected.

By IRWIN MANOIM

T

he largest project of the United Sisterhood was running nursery schools on the grounds of each of the synagogues. The benefits of nursery schools were both educational and promotional: a good way to hook young parents into the congregation. A side benefit is that they gave young mothers, a natural constituency for the Sisterhood, four hours of freedom each morning to do things other than childcare[1]. Unlike the MC Weiler School, in which the Sisterhood had a support-plus-funding role, but had nothing to do with the actual, government-imposed education, the nursery schools were fully their responsibility and they were required to organise everything from fixing the slasto in the garden to hiring teachers to dealing with school inspectors, architects, parents and funding. Key figures in this were Eve Kantor[2], Rae Wilkes (after whom the current Sisterhood building at Beit Emanuel has been named), Rebeccah “Buccah” Jankes[3] and Estelle Rosenberg, daughter of Rae Wilkes.

The first nursery school, at Temple Israel, was founded in October 1949, and was intended as a nursery school for “the children of working mothers, both Jewish and non-Jewish.”[4] Three months later, a second followed, at Temple Shalom. Temple Emanuel’s Hebrew school opened a decade later in 1961, and Temple David’s in 1973. A full-time superintendent ran the schools, aided by a procession of young women who were constantly being replaced, either because they were leaving to have their own children or because they were emigrating. Estelle Rosenberg gave another reason why nursery school teachers did not last: “It wasn’t the children. It was the parents.” None of the teachers seems to have been well paid; committee meetings were constantly weighing up the pressures from parents to keep the fees down against the need to pay the teachers better. [5]

The schools were well equipped with toys, jungle gyms and swings, old cars, cycling tracks, pianos, tiny tot bathrooms with suitably miniature fittings. There seems to have been near constant work at upgrading the facilities and building on new classrooms. The children were regularly being shepherded off to events, including visits to the fire-station or the zoo (“The zoo was my worst,” said Estelle Rosenberg, “all those children running wild and getting lost”.) There was also a visit to the new Lion Park in Krugersdorp, which caused considerable anxiety among some parents, who delayed departure. Only the lions suffered; their feeding was held back until the children eventually arrived. Visits to the Snake Park seemed not to cause the same anxiety. There were also pantomimes at the Alexander Theatre, or educational movies.

Photographs of beaming Sisterhood leaders among happy nursery school children were highlights of the movement’s promotional brochures for many years.

In 1955, the two nursery schools accommodated 120 children. In 1958, the chairman, Eve Kantor, could report that the two nursery schools had to turn away more children than they could accommodate, making the building of a new nursery school at Temple Emanuel all the more urgent. The minutes are annoyingly vague about numbers, but in a discussion in 1966 with the Supervisor of Municipal Nursery Schools, a Mrs Murray, she remarked that she did not like a plan proposed for Temple Shalom by architect Harold Le Roith, because 240 children were being squeezed into too small an area.[6]

But by the nineteen sixties, new problems arose for the nursery schools, and as with the MC Weiler School, they were the creation of the government. A National Education Advisory Council was set up in 1962, and by 1966, had not yet delivered a policy on nursery schools. Nursery schools are expensive to run relative to their numbers of children – they are much smaller than primary and high schools and also require special facilities. As a result, they depended on government subsidies, which the Sisterhood nursery schools, considered among the best, received. [7]

In 1966, the Transvaal Education Department announced that five schools would cease to be subsidised with immediate effect. The explanation was that the continuing uncertainty over national policies had caused them to allocate insufficient funds in their 1966-1967 budgets. One of the five was a Jewish school in Yeoville run by the Board of Deputies; another was the Temple Israel nursery school. Both of the schools, catering to working-class mothers, had to close. Why were Jewish schools a target? Rae Wilkes phoned to ask, and was told that since the Jewish schools were supported by religious bodies and existed for their benefit, those bodies ought to carry the cost of the schools.[8]

A notice was sent to parents of Temple Israel nursery school children telling them that their school was closing as of the fourth term, and that they should send their children instead to the Temple Emanuel Hebrew School, whose expanded premises would open in October. Fees were R20 per term for members, but Temple Israel mothers would receive a fifty percent discount. It’s hard not to suspect that the decision rather suited the UPJC, because it made Temple Emanuel’s nursery school more cost-efficient, and allowed for the Temple Israel nursery school building to be demolished and used for other purposes. How many of the Hillbrow mothers could drop off and fetch children in Parktown was a matter that went unrecorded, but Temple Emanuel’s enrolment was never as high as the other nursery schools.

More than any other records of the Progressive Movement, the nursery school minutes tell, quite unintentionally, a tale of the slow collapse of both white middle-class security and the Progressive Movement itself, in particular after June 1976. In 1971, for example, the fee per term for the nursery schools was R24. Eight years later, in 1979, the fee had jumped to R95, due to a combination of the withdrawal of state subsidies, galloping inflation, and a decline in the number of registrations. Even at R95, the schools claimed to be cheaper than rivals. One also gets a sense of the panic following June 1976.

Suddenly, security concerns were a constant focus, there was an increase in talk about burglaries and there were awkward questions raised by parents about the adequacy of the fencing and about black staff having friends over during school hours. The children were taught emergency drills. They learned to evacuate the schools in two and a half minutes, “in case of riots”. The police were asked for advice on whether the schools should shut on the 16th of June each year. The police answer: “No.” For years the children had their teeth, their eyes and ears and their “school readiness” tested regularly, all courtesy of various city services, but from late 1976 onwards, these dropped off, starting with an end to the dental visits. School outings became less frequent. The once-efficient municipal bus service declined, making the hiring of buses for private outings more difficult. Parents were asked to use their cars, but this proved a logistical and safety nightmare.[9]

Half a dozen teachers resigned during the course of 1977, and most seemed to be emigrating (none, it would seem, to Israel.) Temple Emanuel reported in March 1977 that they would be losing ten families at the end of the first term alone. Two months later, they reported six vacancies for the third term; Temple Shalom reported four vacancies. These were schools that had recently been accustomed to turning away excess pupils. Temple Sinai, in Bedfordview, was about to open a nursery school in early 1977; it was decided to delay this a year. The school never did open – the synagogue itself closed a few months later. The problem was not confined to the Reform community. In February 1977, Rae Wilkes reported back from a Jewish Board of Education meeting at which she learned that the long waiting lists for nursery schools had vanished, that everyone was raising fees, and that everyone was experiencing problems collecting fees.

The ever-pragmatic Buccah Jankes, long-serving chairman of the nursery school board, advised her committee to be on the alert for talk about families leaving the country so that they did not abscond without paying their fees[10]. In her own inimitable words:

“You know, when everybody was leaving South Africa, some of nice Jewish young people were trying to get away without paying the money, the fees. And Ray (Wilkes) and I, we had our spies, we were told who was leaving without paying us. There was one young man living in a posh area and off we went to tell him that there was no going without paying. As we entered the front door there were suitcases all packed and ready to go and out he came and he went somewhat pale, he knew both of us, and I said you know, unfortunately you haven’t paid your fees yet for the nursery school. He said “I‘ll give you a cheque.” I said “No, we don’t accept cheques, I’m afraid you can’t go until you we have the money in cash.” He said “But look, I am ready to go right now.” I said “You have to work that out, but we are going to stay right here until we get the money and then you can go.” So we sat there amongst the suitcases and off he went and came back with the money, and my parting shot was: “Don’t try to do this in America.”[11]

One can also sense the shift in Johannesburg’s Jewish demographics. Those who did not emigrate, “semigrated” to the supposedly safer outskirts of Johannesburg, particularly Sandton, which was then transforming from scattered villages in the countryside into an independent municipality. Temple David in Sandton reported no vacancies in 1977, and an expansion to 110 children. Temple Shalom had 74 children and Temple Emanuel, less than 50. A year later, Temple David pondered whether they should expand to 120 children, or turn 20 away.[12] From that point on, Temple David’s school had as many pupils as the other two nursery schools combined. When Estelle Rosenberg, who had previously run the Temple David nursery school, moved across to run the Temple Emanuel nursery school, she was shocked to find that she only had ten pupils.[13]

Assabi enters the school programme

The final death of the nursery schools was self-inflicted. The controversial Rabbi Ady Assabi (profiles of him in Chapters 23 and 27 of the book) had ambitious plans for a Reform primary school that would feed directly off the nursery schools. His plan was to counter what he perceived as an Orthodox bias in the ethos of the (then) nominally non-partisan King David Schools.[14] In this he was not alone. Reform unease with the King David schools can be traced back to the sixties. When the Sisterhood invited school officials to give talks to nursery school parents, as they often did, they showed a preference for local government schools, and the more liberal private schools like Redhill and Woodmead. A favourite speaker was the prominent liberal educationist Isaac Kriel, who was Jewish, but engaged with secular education. When the Jewish Board of Education, which ran King David School, asked to address a meeting of all nursery school and Hebrew School parents, this was met with suspicion: they only need us now, because their numbers are falling, was a common response.

Assabi hoped to achieve what had already been a dream in the Weiler days: a Jewish day school outside the grip of the Orthodox rabbinate, which instructed children within a non-Orthodox brand of Judaism. It would start off with a junior primary school, based initially at Temple Emanuel, which the rabbi named the Yael Educational Projects after his late wife[15]. The school, opened in January 1991, was to be multi-racial, at that time still a daring and rare decision. To create sufficient critical mass at the nursery school level, he merged the Temple Emanuel and Temple Shalom nursery schools, and shifted the primary school to Temple Shalom. What this meant in practice, was that he closed the Temple Emanuel nursery school, and made Estelle Rosenberg the superintendent of the merged nursery school. But she now worked for him, not for the Sisterhood. The primary school never took off. Parents showed little eagerness to experiment with an untried school, and it failed.[16] Temple Emanuel’s nursery school never reopened, the nursery school equipment was removed, and the tiny tot bathrooms were converted into adult bathrooms. Temple Shalom itself was lost to the Progressive movement not long after, following another bold – but failed – plan by Assabi (see chapter 27 in the book). As Estelle Rosenberg points out, the loss was not merely the nursery schools. What had been closed down was a major entry point for young parents into the Reform movement. They would go elsewhere, and they would be lost.

The opposition speaks: charity begins at home

Not everyone was happy with the United Sisterhood’s activities. There were some who felt that far too much effort was going into outreach activities and that the Sisterhood were not paying enough attention to their duties inside the Progressive Community. Charity was all very well, but what exactly were the women doing to promote membership at their own synagogues? Whether this was a fair criticism is open to debate, but it was an opinion that surfaced more than once. Critics could point to other Sisterhoods in the country, which being much smaller, tended to be more closely bonded to their mother synagogues.

The first rabbi to explicitly interfere in the affairs of the United Sisterhood was Rabbi Aaron Opher, who was the second rabbi (after Rabbi Weiler) to hold the United Progressive Congregation’s title of Chief Minister. His tenure was brief, stormy and contentious. (Discussed in Chapter 19 of the book.) Soon after his arrival from the USA, he told the Sisterhood that they needed to be reorganised on the latest American lines, to make them more efficient. He also felt that their first duty was to support the religious activities of the congregation. His wife Irene, who matched her husband for charm, good looks and bold self-confidence, was inserted into the executive of the Sisterhood. [17]

The rabbi set up a Ways and Means Committee within the Sisterhood, whose purpose was to plan a sweeping restructuring of the sisterhood and its priorities. Mrs Opher had much to say. At the launch meeting of the committee on 26 November 1962, she said the Sisterhood should be building a strong Reform platform from within. She recommended setting targets for fund raising. “She stressed that co-operation of members leads to creative and instructive work and thus develops a well-knit congregation which … makes them conscious of Temple and so goodwill develops.” Her ideas included getting people to contribute to a fund rather than give flowers or presents to people who were ill; “a competition in the form of a passport”, a printed congregational telephone and address directory, paid for by advertising, and a bazaar or fete.[18]

A year later, she was awarded Honorary Life Membership, usually bequeathed only to those who had performed years of hard work. The minutes of the committee are ambiguous in their long-term aims, but the members are politely compliant. There are only the mildest rumblings of discontent: the chairman, Mrs Herman recusing herself from the Ways and Means Committee on the grounds of being too busy; the Temple Emanuel representatives announcing that they had no time to do their duties because they were so busy restructuring.

Rabbi Opher departed suddenly and unexpectedly before his term of office was up, having endured a firestorm of criticism from the Orthodox rabbinate in the pages of the Jewish community press. (See Chapters 19 and 20 of the book). The Ways and Means committee trickled on for a while, before closing down in April 1964. Two years later, when there was talk of bringing Rabbi Opher back, Mrs Herman was rather more explicit about her views: “If Rabbi Opher accepted the position it was pretty obvious that he would make mischief and the worst part of it was that he would be paid to make mischief.”[19]

For a better understanding of the situation, a letter from Mrs Freda Gilder to Rae Wilks, secretary of the United Sisterhood, spelled matters out much more clearly. Mrs Gilder, chair of the SA Union of Temple Sisterhoods, was a long-standing and active member of first the Durban Sisterhood and then the United Sisterhood, and her husband, an ex-president in Durban, was a senior executive on the committees of both the UPJC and the national SAUPJ. Both the Gilders were very close to Rabbi Opher, and it can be assumed that the views expressed in the letter are those of the “Opher faction” as it was called. She wrote:

“My dialogue was really with Rabbi Weiler and his over-emphasis on universalism. We, as organised Jews, still have a tremendous job to do in order to get our own people back to the fold. The danger of assimilation and all that goes with it is so great that it is under constant discussion on world level and the President knows that because she was present at the Board of Deputies when this particular topic came up. I tried to say that we must educate our own people and make them aware of the full implications of Judaism. I tried to say that it was not enough merely to express their Judaism through social service and welfare work, especially as we are first and foremost a religious body, the spiritual and the educational should have priority … I have always maintained and still do, that social service and welfare work is a fragmentary part of the work of a Jewish Religious Body and not the dominating factor. There is much to be done for our own people, and no-one else will do it.”[20]

A year later the president, Mrs Jewel Skok, got her own back. The tide had swung against the Opher faction when they started their own congregation in mid-1965 (See the book, Chapter 21), and Mrs Skok in particular was ruthless in rooting them out. First, she had Mrs Gilder expelled from the local Temple Emanuel committee, probably unnecessary since she had already left. Then in November at the national AGM, she claimed that “too many irregularities had occurred and would continue to do so as long as Mrs Gilder is the president”, and threatened to withdraw the United Sisterhood entirely from the SAUTS.[21]

Much the same sentiment as Mrs Gilder’s was expressed a dozen years later by Maurice Silverman, President of the UPJC, who met with the Sisterhood in April 1977 to complain that they were not doing enough for the congregation.

“The Sisterhood as far as I am concerned is the women’s wing of the congregation and we would like to see Sisterhood doing things not only as individuals but as a Sisterhood within the Congregation to make themselves known inside. I feel that a lot of our members just don’t appreciate what the Sisterhood is because they see it as another welfare body, and a lot of the Sisterhood members don’t think of themselves as part of the Congregation as they are doing a first class job for a cause. Ongoing through your Annual Report you mention all the activities. Now if we didn’t know that the Sisterhood was part and parcel of a Congregation you could be just as easily a Union of Jewish Women or a Vroue Federasie. The work that is being done by the Sisterhood, although it gives us a lot of good publicity, is not connected with the Congregation.”[22]

Millie Wayburne and Rae Wilkes attempted to explain that the Sisterhoods came in two parts: there was the United Sisterhood which did social outreach projects and ran the nursery schools, and there were local Ladies Committees at each synagogue which were “parochial bodies” that only worked for their Temple. Mr Silverman was not convinced. “We are trying to promote a positive religious Reform Judaism. I can only think of Mrs Celliers at the Sisterhood Sabbath. When this woman got up and recited her prayer I felt that here is a committed woman – committed to Christ in her case, or committed to God if you like. She got up there and I think she’d be welcome to the pulpit in this Temple on any occasion that is required. We haven’t got very many women in the congregation who are so committed. Rhona Lubner, who is a Sisterhood through and through, attends each and every service and she is committed very deeply to her Judaism, but she does nothing else in the congregation except the flowers which is a Sisterhood activity … but she’s not interested in the educational side. Now, if the Sisterhood could encourage people like that or get more people to be like her from the religious side. We like to see the faces of the women in the shul as well as the men.”

Buccah Jankes, left and Ray Wilkes were the key personalities behind the nursery schools. They are here with United Sisterhood leader Joy Raphaelly

A miniature Friday night Kiddush with candles and grape juice for wine

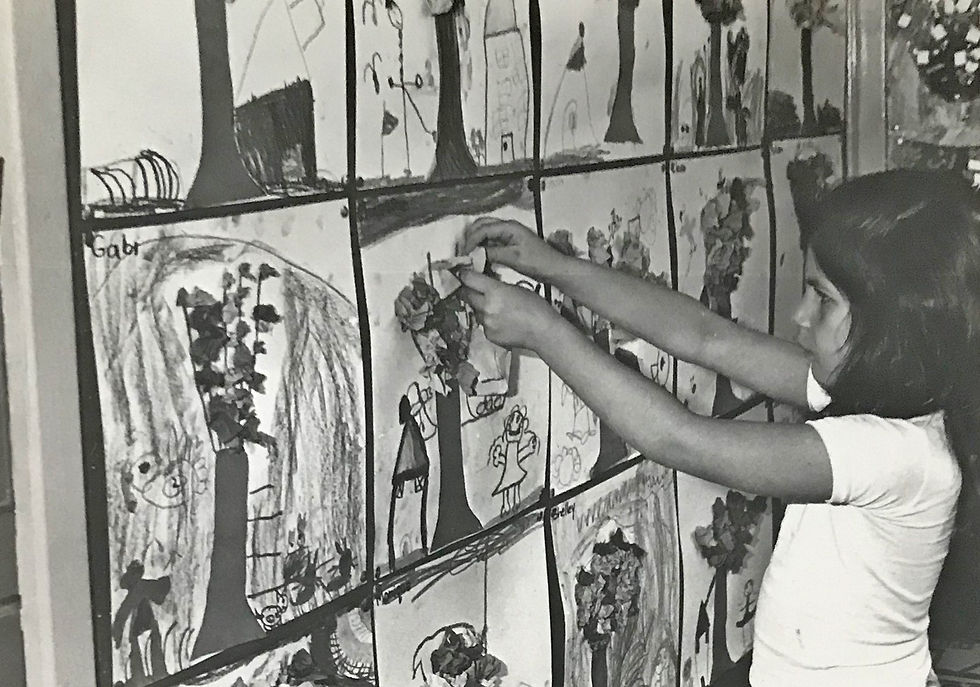

The very serious matter of hanging up paintings for show

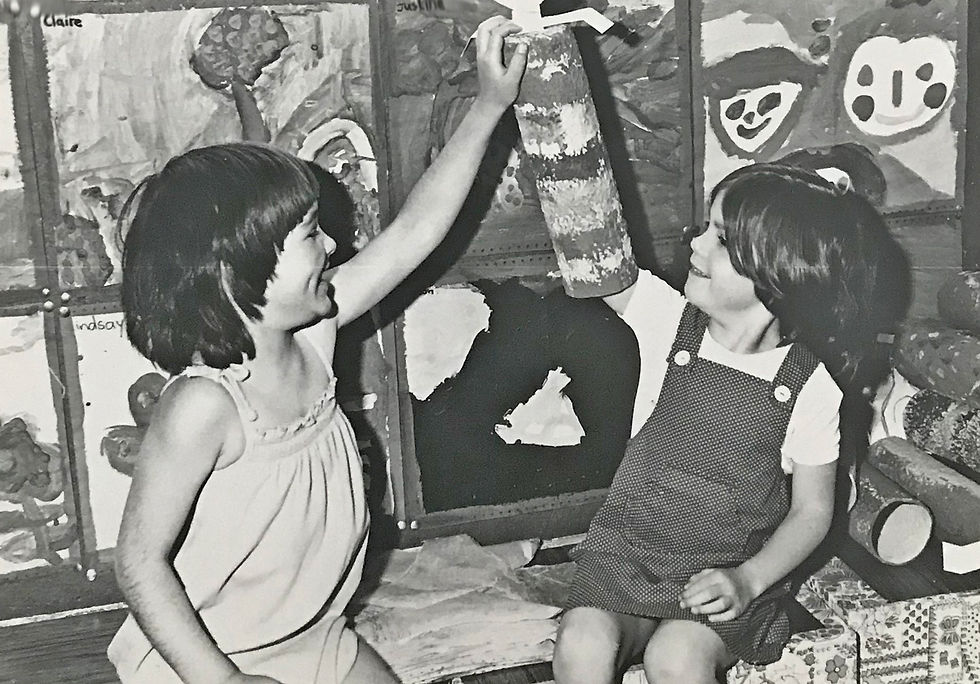

Relaxing after the hard work of a day's painting

Hard at work with the paint brush, Lynne Jacks and Heidi Galgut

Children and teachers on the lawn at Temple Emanuel nursery school in Parktown

The unfenced early nursery school at Temple Israel. Hillbrow, in the background, consists of modest single storey houses

Notes

[1] Education Department rules prevented nursery schools from operating more than four hours a day, usually 8.30 to 12.30.

[2] Chair of the United Sisterhood five times between 1956 and 1966. She also started the Golden Age Friendship Club in 1956, which offered entertainment to pensioners, Jewish or not, and continues to this day, named after her. Other Sisterhoods, notably Cape Town, have run successful programmes for pensioners.

[3] United Sisterhood chair in 1970 and 1971, and long-time schools superintendent.

[4] Sisterhood Activities through 21 Years. Brochure of the Sisterhood of the United Jewish Reform Congregation of Johannesburg, 1954.

[5] Buccah Jankes remarked that “Rae Wilkes was the secretary … she was the most loyal, devoted human being. But I think she was hardly paid at all.”(Interview with Buccah Jankes, 24 September 2017.) Estelle Rosenberg remarked that she hated the Sisterhood as a child, because her mother seemed to spend her entire life as a slave to the cause. (Interview, 09 December 2017).

[6] The site, at Temple Shalom, was long, narrow and sloping, explained Le Roith, who settled on four separate units. 16 June 1966.

[7] Nursery schools were often set up by parent bodies, but cost R25 000 just to build, which was why subsidies were essential. (The Star, 15 August 1966.)

[8] According to a note from Rae Wilkes, 17 June 1966, following a telephone conversation with the authorities.

[9] Interview with Estelle Rosenberg, 09 December 2017.

[10] Minutes of the Nursery Schools Management Committee, 28 March 1977.

[11] Interview with Buccah Jankes, 24 September 2017. She also told how she bragged to the children that she had been in an aeroplane to Cape Town, and some replied that they’d been in aeroplanes to Australia.

[12] Figures based on Nursery School Management Committee minutes from July 1977 to August 1978.

[13] Interview with Estelle Rosenberg, 08 December 2017. She ran Temple David until falling pregnant; she returned to Temple Emanuel when her children were old enough. She rebuilt the numbers over time.

[14] Based on the interview with Estelle Rosenberg, op cit, 08 December 2017.

[15] Yael Assabi, who died young, was a lawyer who worked in the rehabilitation of teenage criminals in Israel.

[16] Lesley Rosenberg said she rebuffed similar attempts by Assabi to take over the more successful schools at Temple David. (Interview, October 2017).

[17] Not entirely unusual. Bertha Sherman, wife of Rabbi David Sherman in Cape Town, Tilly Super, wife of Rabbi Arthur Super, Heather Mendel, wife of Rabbi Norman Mendel, were among a number who played prominent roles in the sisterhoods.

[18] Ways and Means Committee, 28 November 1962.

[19] UPJC Council Meeting, 22 June 1965.

[20] Letter dated 2nd December, 1964. United Sisterhood Archives.

[21] The UPJC also tried, unsuccessfully, to have another of the Opher supporters, Mrs Dora Miadownik, removed from office.

[22] Special meeting at Sisterhood Office, 14 April 1977.